The pace of global economic growth peaked in the second quarter of 2021. As we alluded to last month, the ‘explosive’ stage of the recovery now seems to be behind us at an aggregate level. Growth remains strong and above trend, but it is decelerating.

There is increasing evidence of regional disparity in current growth rates. The US is only now starting to slow whereas European growth could still accelerate further in the second half of the year. Asia is looking problematic as several economies are struggling to cope with the sharp rise in Delta variant cases.

Meanwhile, China’s growth trajectory continues to slow, in part due to a regulatory clampdown but also renewed problems with the virus. While robust at the aggregate level, the global picture is becoming more fragmented and decoupled regionally.

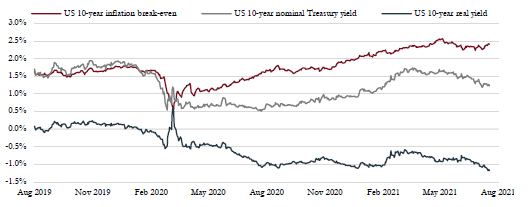

Inflation data is little changed over the past month. We see no reason to change our view that the long-term inflation regime is intact and that the current spike will pull back to trend levels of 2% to 2.5% in the next three to six months.

Monetary policy is moving at a very slow pace. The US Federal Reserve (Fed) seems the only large central bank likely to make any changes to policy in the near term. Policymakers will probably announce that they will taper the quantitative easing (QE) programme by the end of the year. But rate hikes still seem a long way away.

If our concerns about Asian growth are confirmed then that might prompt the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) to ease policy (policymakers have already cut the bank’s reserve ratio). A renewed credit cycle could be positive for Asian assets.

Above-trend growth depends partly on a robust capital expenditure cycle, especially in the US. Given the level of corporate cash, interest rates, inflation and real yields, we believe there is a strong case for such a cycle to emerge. This could sustain positive earnings surprises into 2022.

The clear risk to this above-trend growth thesis is that the Delta variant creates further disruption to supply chains, particularly in Asia, interrupting the capital expenditure cycle and perpetuating high inflation for longer than expected.

Investor are shifting attention towards the economic outlook and the possibility that the pace of growth may fade more quickly than expected, as implied by the recent drop in bond yields.

China’s clampdown

Over recent months we have seen Chinese regulators step up the crackdown on some of its largest domestic companies. One side effect is that the country’s stocks markets have fallen this year and underperformed global indices by over 15%.

Initially it seemed the regulator’s ire was directed primarily at tech and internet names after the high-profile Ant Group IPO debacle and the recent calamitous Didi listing in the US (China’s version of Uber). But the government’s goals now appear far broader.

This became clear after the enforcement of regulation that obliged education companies to convert to not-for-profit organisations, as well as closing off foreign investment to them. This wiped out over 90% of the sector’s market value.

More recently there have been restrictions enforced on Tencent aimed at reducing the time young people spend gaming, as well as on Meituan over worker pay and monopolistic behaviour. There have also been regulatory probes launched into how data is being used by a number of internet-related companies.

Last December’s Politburo meeting now looks to have been a significant policy inflection point. Tying together these regulatory moves with recent PBoC and ministerial actions paints a picture of conformity in Beijing’s new objectives of targeting ‘common prosperity’ in the next stage of development. The policy aims for a more equitable society, to promote fairness and competition, and continued support for smaller and private companies, as well as prioritising data security and sustainability.

Relations between China and the US are tense with Chinese foreign stock listings under scrutiny with regard to their auditing standards and risks of Chinese government interference.

It is important to remember that macro-prudential regulations have been, in general, on a tightening path since 2016 in order to promote financial stability. But it has become clear that Beijing’s efforts to reshape the economy take priority over shareholder interests and this has soured investor sentiment, which may take some time to recover.

Macro-prudential regulation is only part of China’s economic policy toolkit. Monetary and fiscal policy are also important and it is possible that monetary policy may adjust to offset some of these regulatory headwinds.

Having rebounded from the pandemic first and seen economic slowing in recent months, China’s credit impulse is nearing a cyclical trough. While this doesn’t guarantee that rate cuts are imminent, the July reduction in reserve ratios for the banks may be a step toward easier policy.

In this context, we view the current overall policy stance as shifting from tightening to perhaps a modest easing. These may accelerate given recent Covid developments and localised lockdowns in China.

China’s equity risk premium has risen sharply and the equity market now looks relatively cheap. This is likely to persist given the regulatory risks, but we think much of the correction in prices has already occurred and now reflect the political reality.

Mid-cap domestic companies are less exposed to regulatory interference and US listing angst. We are increasing our exposure to this part of the Chinese equity market as growth prospects and valuation remain attractive there.

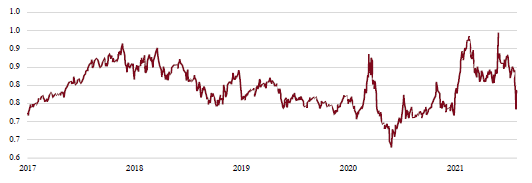

MSCI China relative valuation- China’s stock market has suffered a fall in valuations compared with global markets owing largely to the government’s restrictions on some industries.

Source: Saranac Partners

Sentiment is riding high

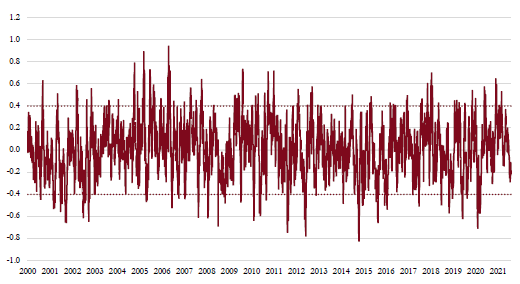

As some markets hit new highs, we wanted to look at investor sentiment and understand if ‘animal spirits’ are dangerously high. Most market sentiment studies show few warning signals – optimism is generally high but far from extreme.

Risk sentiment – Our proprietary risk sentiment indicator shows that despite indices hitting all-time highs, market sentiment doesn’t appear exuberant.

Source: Saranac Partners

The rotation back into growth stocks has seen market concentration deteriorate somewhat. Mega-cap names are outperforming again and the breadth of the market is not as strong as it was earlier in the year. This concentration of performance means that the majority of companies are below their recent highs, despite the progress made at the index level.

Business and consumer sentiment is undeniably strong as credit conditions remain very favourable and the employment outlook is improving. We don’t see over-optimism as a risk to markets at this stage of the cycle.