At the beginning of the year, we highlighted some of the key market dynamics we were thinking about, foremost being the debate over growth and the efficacy of vaccinations in allowing economies to return to ‘normal’. The answer was unequivocal as growth exploded in the second quarter and vaccinations proved effective such that much of the Western world moved on to thinking about living with Covid rather than trying to eliminate it altogether.

The debate has now progressed to consider the extent to which that explosive growth is likely to slow, and whether or not the resultant imbalances between demand and supply will have long-term implications for inflation. We have been spending a lot of time questioning the inflation outlook.

In particular, there is growing concern that the inflation we see today could prove to be less transitory than central banks would have us believe. The prospect of high inflation combined with slowing growth has led to a sudden surge in the topic of stagflation across the media.

It is still the case that supply chain disruptions are forcing producer prices higher. A shortage of shipping containers, skyrocketing shipping rates, congestion at ports and a dearth of truck drivers are contributing to push up input prices. There are also high-profile shortages in sectors such as semiconductors, which are having a disproportionate effect on some industries. They include auto manufacturers where production rates have fallen sharply and prices of new and used cars are rising.

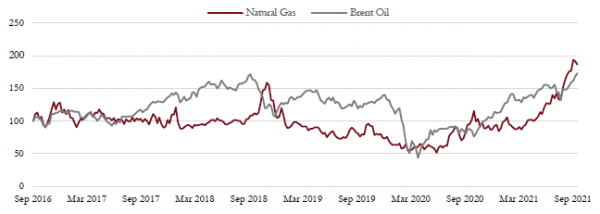

In addition, over recent months there has been a vicious squeeze on energy prices, here in the UK and across Europe but also in Asia and China in particular. Natural gas and coal prices have hit record highs and volatility in these commodity prices have soared. Consumers and many industrial companies are facing painfully higher energy and fuel costs over the winter months.

Labour markets are out of balance

Furthermore, imbalances are not restricted to just the global supply chain and energy markets. Labour markets continue to struggle to correct their own imbalances as unemployment rates remain higher than they were pre-Covid in most developed markets.

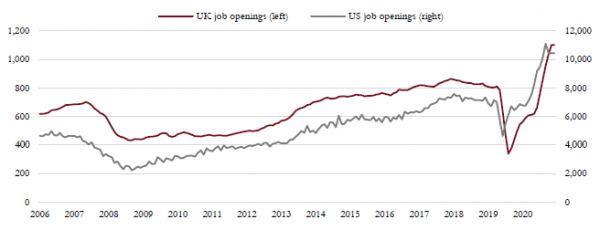

Yet employers complain of a chronic shortage of suitable labour for job openings. For example, UK job vacancies topped 1 million for the first time ever in the three months to August. Meanwhile, vacancies in the US rose to 10.9 million in July, according to the JOLTS survey, which is also a record.

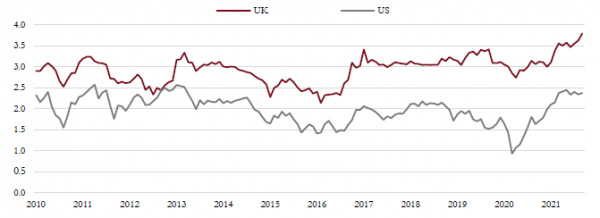

This tightness in the jobs market is seeing wage inflation respond accordingly – wages are rising at a rate not seen in many years. They are up 4.3% in the US over the past year and they’ve risen 6.8% in the UK in the three months to June compared with last year.

Investors are questioning whether these supply shocks are sufficiently large and widespread to make a permanent difference to the inflation picture going forward. We have our doubts, as many of the arguments for higher inflation highlighted above have strong counterarguments.

Job vacancies in UK and US – Employers on both sides of the Atlantic are finding it difficult to find workers even though unemployment rates remain relatively high.

Source: Saranac Partners.

There is an important distinction between a one-off adjustment in prices, caused by supply shocks, and persistent and pervasive inflation. A shift to a different regime of high inflation implies that the price pressures we are seeing now are continuous and will still be in force next year.

Base effects here are an important consideration. High inflation levels today are partly a consequence of very depressed prices this time last year. As we roll forward into 2022 these comparisons will look very different. Energy prices are now up over 100% compared with last year, and it is highly likely that their contribution to overall inflation next year will be significantly lower, if not negative.

Although they are painful, supply chain bottlenecks are likely to gradually resolve themselves. Shipping rates should fall as capacity comes on-line, ports will function more normally as Covid restrictions ease (in part due to vaccinations) and other disrupted forms of transport, such as air cargo, will come back on-line as international air travel resumes.

Shortages in the semiconductor space are expected to clear over the next two quarters, allowing production rates for autos to normalise and pricing to be more competitive. Lastly, labour markets are expected to continue to repair and the labour force expand again as generous benefit programmes end, schools reopen and parents are able to return to the workforce, and important sectors such as hospitality and leisure come back on-line.

Inflationary pressures are likely to fade

All of these factors make a strong case for inflationary pressures to wane next year and the current environment to prove transitory. However, changes to labour market structure and global supply chains could result in inflation settling at a higher level than was prevalent pre-Covid, but this may be no bad thing given inflation has typically fallen short of central bank targets over the past decade.

Our scenario probabilities recognise that the outcome is not clear cut and there is a risk that price pressure could lead to a more permanent and meaningful shift in wage expectations. Wage inflation is the most important factor when considering future inflation. It carries far more weight than commodity price inflation, and a rising spiral of wage demands and wage pressure would be a significant development.

The past three decades has seen a gradual shift of economic value from workers to companies, as witnessed by the rising margins enjoyed by most companies. A reversal of this trend would be important with regard to equity market valuations.

It is important to note that inflationary expectations, as set by the market, have remained contained throughout this period, with the recent exception of the UK. The country has its own set of economic challenges, which are exacerbating supply disruptions and may take longer to resolve.

Inflation has been spiking higher recently – Supply shortages and transportation challenges are just two of the factors pushing up the prices of products around the world.

Source: Saranac Partners.

Although the pace of economic growth is slowing, it is still well above the long-term trend and this slowdown was inevitable from the torrid pace seen in the second quarter. Aggregate demand looks robust as economies reopen and consumers have accumulated significant savings over the past 18 months, which should keep economic growth buoyant and we believe it will remain above trend well into 2022. This is not the outlook of a stagflationary environment and we think concerns about a return to no growth and high inflation are misplaced.

China’s economy faces a number of challenges

China has been an important topic recently. The pace of economic growth has slowed sharply, the government has tightened the regulatory backdrop, a prominent real estate company has defaulted on its debt and the country is facing meaningful energy shortages. These challenges have caused the Chinese equity market to fall 5% this year, underperforming global equity markets by 15%.

We have meaningful exposure to the Chinese market, which has hurt performance this year. We analysed the exposure of our total equity positions and find that 14% of their aggregate revenues derive from China. Given China represents about 19% of global GDP, this does not look high and the data is somewhat skewed by the fact that we hold two China stocks where the vast majority of revenues are domestic.

However, we also find that a quarter of our individual stock holdings have China revenues that are between 20% and 80% of their total revenues, and so can be considered sensitive to Chinese trends. We believe our exposure to China is appropriate in the overall portfolio context, particularly as we think its economy is now closer to a trough than a peak and could become a more positive contributor to returns in the near future.

Commodity markets have been volatile

Imbalances within the commodity markets have been a significant source of inflation stress this year and natural gas in particular has become the poster child for supply shortages and price squeezes. We think there are a number of idiosyncratic problems facing some of the energy markets now. High demand has been one issue as economies have reopened and looked to make up lost ground.

However, there have also been disruptions to supply, in particular within the renewable energy sector as wind power in Europe and hydroelectric power in China have fallen well short of expectations. This situation has raised the important question of security of energy supply and the challenges facing the global economy in its transition away from fossil fuels. In the meantime, it has created price disruptions in energy markets that contribute to the overall inflation picture today.

Energy costs are rising – Both natural gas and oil prices have increased recently for a variety of reasons.

Source: Saranac Partners.

Commodity markets are cyclical and high prices usually lead to increased supply and lower prices. Although we believe this relationship remains true, the supply response may be less rigorous than has been the case in the past as the energy sector has seen access to capital become increasingly difficult.

Environmental pressure on the sector is seeing capital allocated more towards renewable sources of energy, while the financial sector is becoming constrained in its ability to lend to the energy sector due to environmental concerns. This may lead to long-term energy prices being higher than previously forecast, although we think they will fall over the next year.