The global spread of Covid-19 has stopped the embryonic economic upswing in its tracks. A sharp contraction in activity now seems inevitable as a growing number of countries take dramatic steps to contain the virus.

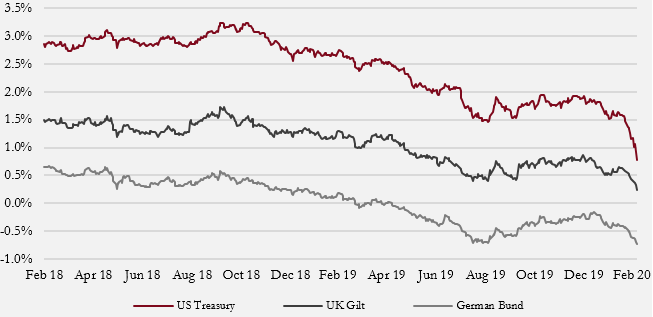

We highlighted market complacency over the outbreak in China last month, and risk assets corrected sharply as the virus spread to other countries. Global equities fell over 12% in less than a week, while safe-haven assets rallied strongly, including government bonds and gold.

Our questions now focus on the possible outcomes for the global economy in response to the efforts to contain the virus, and to what extent market movements have already discounted these possibilities.

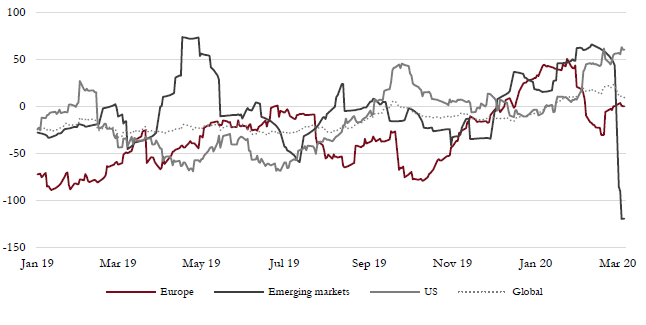

For several months we had been encouraged by signs that the global economic downturn, which began in early 2018, was coming to an end and a new upswing in growth was upon us. This narrative has now collapsed as economic growth has turned sharply negative in certain regions, in particular China, due to the steps taken to contain the spread of the coronavirus (figure 1). These measures have essentially cut off the supply of labour to many parts of the economy.

Figure 1: Economic surprise indices

Economic indicators had been coming in ahead of consensus forecasts but the collapse in Chinese data is an early signal of the deterioration to come globally.

Source: Bloomberg.

Given China’s importance to the global economy (16% of global GDP) and its integral role in the global supply chain, the damage to growth in other parts of the world is also likely to see economic growth rates turn negative in much of the developed world.

The rapid spread of the virus to other countries such as South Korea, Singapore, Iran and Italy has now compounded the problem and the potential negative impact to growth is now more significant.

The extent to which the global economy contracts is now highly uncertain and it is this uncertainty that triggered the sharp correction in risk assets.

Scenario 1:

The growth rate of recorded instances in countries already infected peaks in the next three to four weeks and follows a similar pattern to China, with new cases dropping sharply. The coronavirus does not spread to other parts of Europe, Asia or North America and activity rebounds to more normal levels early in the second quarter as the situation is deemed to be under control. Economic data holds up and there is a rapid pick-up in growth.

Scenario 2:

The virus spreads to other parts of Europe and North America and the growth in recorded cases peaks in two to three months, resulting in a more damaging contraction in activity for a more prolonged period. First-quarter data is weak and second-quarter economic data is worse, but we see a robust rebound in growth in the second half of the year, boosted by monetary and fiscal policy response, and the global expansion continues.

Scenario 3:

The virus spreads to other parts of the world and proves difficult to contain, leading to a deep and prolonged contraction in economic growth. The disruption to activity results in a spike in bankruptcies, credit conditions tighten significantly and the global economy falls into recession as unemployment rises and concerns rise over leverage levels.

Market implications for these different scenarios vary significantly. In scenario 1 markets are likely to rise from here as the correction has already discounted the bad news. Bond yields would also rise (and prices would fall). Scenario 2 could see continued volatility in the coming weeks and the possibility of another correction that would take equity markets 15–20% lower than their highs and widen credit spreads. In scenario 3 a bear market in equities (down 30–40% from their highs) is likely, with lower bond yields but wider spreads, and gold prices could rise significantly.

We place the overwhelming probability on scenario 2 (70%), but recognise that both the positive and negative outcomes are also plausible.